Dry eye and cosmetics: what does the research tell us

The quest to enhance human beauty with eye makeup began thousands of years ago. Today it continues with an unremitting passion. But there is a dark side to cosmetics. Over 12,000 chemicals are used in these formulations. Many of these compounds are synthetic and industrial chemicals and less than 20% have been shown to be safe¹. A number of ingredients in these products may act as allergens, carcinogens, endocrine disruptors, immunosuppressants, irritants, mutagens, toxins and/or tumour promoters, and may damage the ocular surface. Indeed, multiple adverse reactions to eye cosmetics may occur, including dry eye disease (DED)1,2.

Many of the chemicals used in eye makeup are preservatives to prevent bacterial, yeast, mould and/or fungal contamination. Two of the most common are benzalkonium chloride (BAK) and parabens, which appear in eyeliners, eye shadows, mascaras and serums. BAK application may induce irritating, burning, itching and foreign body sensations on the ocular surface and cause meibomian gland and goblet cell loss, tear film instability and DED. It is remarkable that BAK concentrations 20,000-fold lower than approved levels in cosmetic products are toxic to human corneal, conjunctival and meibomian gland epithelial cells in vitro1,3. Parabens serve as preservatives in more than 22,000 cosmetic items in the US and high urinary levels of ethylparabens and methylparabens have been associated with the signs and symptoms of DED1,2. These compounds are endocrine disruptors and possess antiandrogen activity and oestrogen potency. Androgen deficiency is a major risk factor for the development of meibomian gland dysfunction and DED, whereas oestrogens may promote these conditions4.

Numerous other ingredients in eye cosmetics may also elicit significant adverse effects. Two examples are prostaglandin analogues and tea tree oil (TTO). Synthetic prostaglandin analogues are present in over-the-counter eyelash growth serums and their use may increase the risk of meibomian gland dysfunction and DED2. TTO, in turn, and its most active ingredient, terpinen-4-ol (T4O), are often used to treat ocular demodicosis. The American Academy of Ophthalmology recommends a daily lid scrub with 50% TTO and lid massage with 5% TTO ointment to treat infestation5. TTO and T4O, at concentrations up to 1%, are also included in eye makeup removers, moisturisers, toners and cleansers for eyelids, eyelashes and eyelash extensions. However, chronic exposure to eye makeup products containing TTO and/or T4O may lead to toxic sequelae. TTO is also an endocrine disruptor and possesses anti-androgen (0.005% TTO) and oestrogen (0.025% TTO) activities, leading to hormonal effects that may cause meibomian gland dysfunction and DED. Indeed, treating human meibomian gland epithelial cells with 1% T4O killed all the cells within 90 minutes in vitro, while reducing the T4O concentration 10-fold to 0.1% killed most of the cells within one day. TTO may also promote antibiotic resistance and allergic contact dermatitis. People should be cautioned about repeated exposure to TTO or T4O, given they may apply eye cosmetics containing these ingredients multiple times a day, every day, for weeks, months and years6.

There are many cosmetic procedures for the eye, including curling, dyeing, tinting and perming of eyelashes; injecting botulinum toxin, filler or platelet-rich plasma; piercing and tattooing of the conjunctiva and eyelids; resurfacing and tightening of skin; and using chemical peels, microdermabrasion and microneedling. These procedures may also be associated with adverse ocular events and DED2. Unfortunately, relatively few people are aware of these ocular hazards.

It is important to understand that the use of eye cosmetics is a lifestyle challenge. Eye cosmetic products and procedures may have multiple adverse effects, which may harm and/or promote the development of ocular surface and adnexal disease2. Eyecare practitioners and consumers need to be educated about the medical risks associated with eye cosmetic products and procedures2. We also need far more research to determine the acute and chronic effects of eye cosmetic ingredients and procedures on the ocular surface and adnexa2.

In closing, since before the age of antiquity (~3000BCE) individuals have applied eye makeup ‘to speak with the eyes’2,7. We need to protect that speech.

NB: This article highlights certain sections from reference 2, part of the Tear Film & Ocular Surface Society Workshop, entitled ‘A Lifestyle Epidemic: Ocular Surface Disease’, which addressed the direct and indirect impacts that everyday lifestyle choices and challenges have on ocular surface health. I thank all my co-authors on that report

References

- Wang J, Liu Y, Kam W, Li Y, Sullivan D. Toxicity of the cosmetic preservatives parabens, phenoxyethanol and chlorphenesin on human meibomian gland epithelial cells. Exp Eye Res. 2020 Jul;196:108057.

- Sullivan D, da Costa A, Del Duca E, Doll T, Grupcheva C, Lazreg S, Liu S, McGee S, Murthy R, Narang P, Ng A, Nistico S, O’Dell L, Roos J, Shen J, Markoulli M. TFOS Lifestyle: Impact of cosmetics on the ocular surface. Ocul Surf. 2023 Apr 13;29:77-130.

- Chen X, Sullivan D, Sullivan A, Kam W, Liu Y. Toxicity of cosmetic preservatives on human ocular surface and adnexal cells. Exp Eye Res. 2018 May;170:188-197.

- Sullivan D, Rocha E, Aragona P, Clayton J, Ding J, Golebiowski B, Hampel U, McDermott A, Schaumberg D, Srinivasan S, Versura P, Willcox MDP. TFOS DEWS II Sex, Gender, and Hormones Report. Ocul Surf. 2017 Jul;15(3):284-333.

- www.aao.org/eye-health/ask-ophthalmologist-q/tea-tree-oil-demodex-mites.

- Chen D, Wang J, Sullivan D, Kam W, Liu Y. Effects of Terpinen-4-ol on Meibomian Gland Epithelial Cells In Vitro. Cornea. 2020 Dec;39(12):1541-1546.

- Murube J. Ocular cosmetics in ancient times. Ocul Surf. 2013 Jan;11(1):2-7.

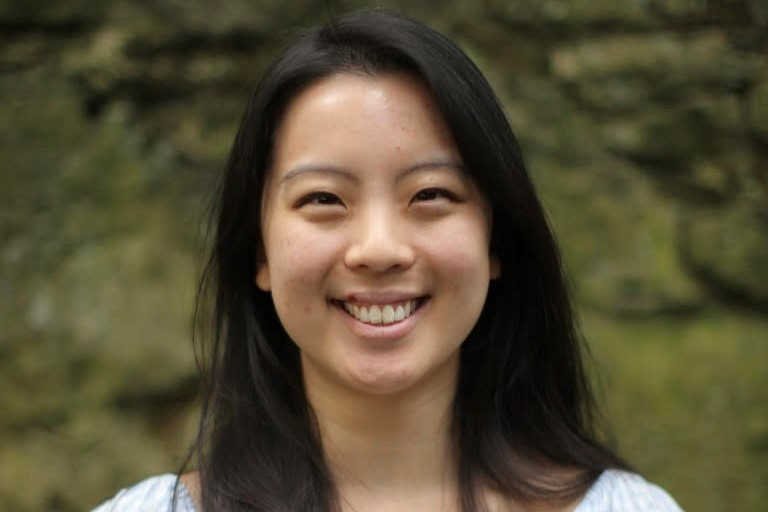

Associate Professor David Sullivan is a co-founder and current chair of the board of TFOS and organiser of the TFOS Lifestyle Workshop. He is a former associate professor in the Department of Ophthalmology at Harvard Medical School and a senior scientist at the Schepens Eye Research Institute in Boston.